Blue on black,

tears on a river

Push on a shove,

it don't mean much

- 'Blue on Black', Kenny Wayne Shepherd Band

Don't mean much? Take a look at the colours of the Ulysses butterfly (

Papilio ulysses) from Australia's tropics and say that again. The amazing contrast between the two regions of this butterfly's wings is actually teaching us some things about optics that we didn't realise.

The butterflies are actually doing two separate things - creating not only the brightest blue, but also the blackest black to make the contrast as strong as possible.

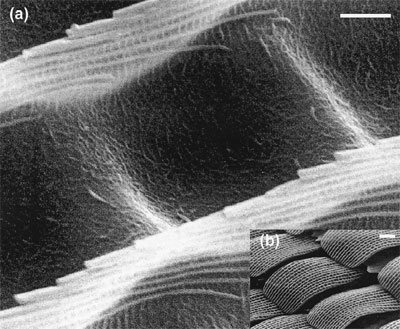

You can just see the tiny scales that coat the surfaces of the wings in the photo on the right. But each of those scales is covered with further structures so minute that they actually do strange things with the light that hits the scale. Take a look at the structure of those matt black scales.

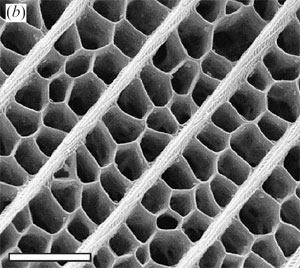

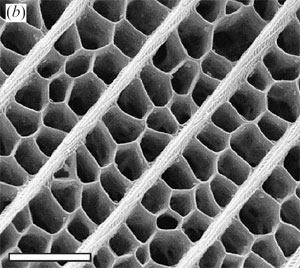

From Vukusic et al. (2004, Figure 2b). This is a scanning electron micrograph of the ridges and latticing on a scale (bar represents 2 μm). While there's black pigment on the surfaces and interspersed throughout the material, this pigment can only absorb so much light. The rest is reflected. But the structure is such that the light actually seems to bounce around in those pits (which are tiny; a thousandth of a millimetre across by my estimate) and get scattered towards the absorbing pigment, some of it getting absorbed each time it encounters the pigment. The end result is an absorbance as high as 95%. This is actually the first time that the use of microstructures to create black colouration has been demonstrated.

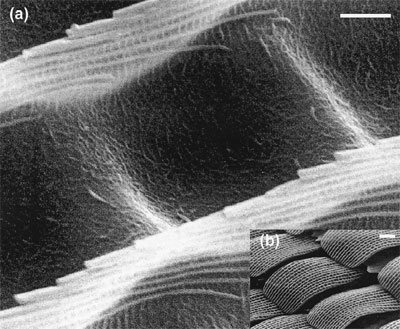

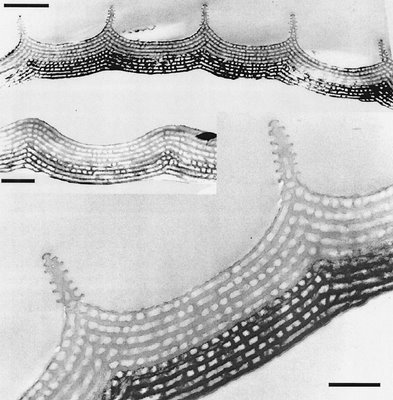

Now take a look at the fine structure of the blue scales (right; from Vukusic et al, 2001; fig. 3; scale bars: a: 1 μm, b: 20 μm). Those ridges are still there though the complex pits within them are not. So it's not really the surface structure that's responsible for the brilliant azure.

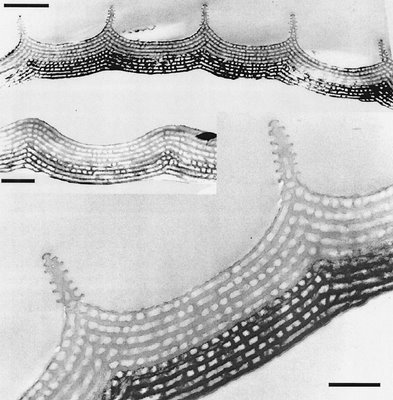

Also from Vukusic et al, (2001, figure 5, scale bars from top: 3 μm, 1 μm and 1 μm), this final figure shows some cross-sections through the scale. The physics is a bit complicated and I don't understand it fully myself, but from what I gather, the 3D matrix of air-filled spaces (often referred to as a 'multilayer nanostructure') within the scale leads to a phenomenon called 'coherent scattering'. So some wavelengths undergo interference and are 'cancelled out' while others are reinforced (i.e. the blue).

So there it is. A great illustration of two completely different types of structural colour and how they are used to produce a conspicuous distinction between a bright colour and its background. Blue on black never looked so amazing.

References: Prum, R. O., T. Quinn, and R. H. Torres. 2005. Anatomically diverse butterfly scales all produce structural colours by coherent scattering. The Journal of Experimental Biology 209:748-765.

Vukusic, P., J. R. Sambles, and C. R. Lawrence. 2004. Structurally assisted blackness in butterfly scales. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B (Biological Sciences), Biology Letters 271:S237-S239.

Vukusic, P., R. Sambles, C. R. Lawrence, and G. Wakeley. 2001. Sculpted-multilayer optical effects in two species of Papilio butterfly. Applied Optics 40:1116-1125.

I'm sleepy. Just an image for tonight. It's a small species of native bee that visits my garden frequently, one of the Lipotriches species. I think it's L. excellens, though flavoviridus is another possibility. It's foraging on a Lobelia flower.

I'm sleepy. Just an image for tonight. It's a small species of native bee that visits my garden frequently, one of the Lipotriches species. I think it's L. excellens, though flavoviridus is another possibility. It's foraging on a Lobelia flower.