The only IDs I'll attempt are:

No. 3: Lipotriches sp.

No. 4: Yellow-spot bee (family Colletidae, Amphylaeus, Hylaeus or Meroglossa sp.) plus

Camera batteries are charged and I'll have another go when the weather fines up.

My photos of the natural world's inhabitants, juxtaposed with what I've discovered about them.

The phasmid species that I wrote about that showed phase change appears to be Didymuria violescens. This photo is of an adult male - I also have some females that have just reached adulthood.

The phasmid species that I wrote about that showed phase change appears to be Didymuria violescens. This photo is of an adult male - I also have some females that have just reached adulthood. Snail mentioned "cheese-skippers", the jumping maggots of the carrion flies (Piophilidae).

Snail mentioned "cheese-skippers", the jumping maggots of the carrion flies (Piophilidae).It's slightly less obvious why piophilids are called cheese-skippers. You need to see the maggots at work before the common name makes sense. When disturbed, they curl up, grabbing their ... ahem ...anal papillae with their mouthparts. And then they let go, springing several centimetres into the air. Boo!Jumping in dipteran larvae additionally occurs in several other, taxonomically diverse families. These include Tephritidae (fruit-flies), Cecidomyiidae (gall midges), Agromyzidae (leaf miner flies), Clusiidae (umm...?) and Phoridae (scuttle flies). (Phew, those are a few fly families that you don't come across very often! I wouldn't know a cecidomyiid from Adam!).

That's a female pictured on the left; males are more slender and elongate. They fight head-to-head, striking each-other with their front legs, heads and antennae. Males also put those long legs to use standing guard over a female - literally.

That's a female pictured on the left; males are more slender and elongate. They fight head-to-head, striking each-other with their front legs, heads and antennae. Males also put those long legs to use standing guard over a female - literally. This photo shows what a larva looks like before (left) and after (right) evacuating its gut. Only when it's done this does it gain the ability to jump.

This photo shows what a larva looks like before (left) and after (right) evacuating its gut. Only when it's done this does it gain the ability to jump. This image was taken a couple of months ago of a species called the Whirring Treefrog, Litoria revelata, from the mid-north coast, where it's relatively abundant in some areas, though it's not a commonly encountered frog in general.

This image was taken a couple of months ago of a species called the Whirring Treefrog, Litoria revelata, from the mid-north coast, where it's relatively abundant in some areas, though it's not a commonly encountered frog in general. Esmeralda cove

Esmeralda cove Green and Golden Bell Frog (Litoria aurea) on prickly pear

Green and Golden Bell Frog (Litoria aurea) on prickly pear Bell frog on algal mat

Bell frog on algal mat

Spotted this tiny fellow hanging on between a couple of blades of grass/sedge by the edge of a large pond a few weeks back. It was in the process of metamorphosing and still had a significant tail.

Spotted this tiny fellow hanging on between a couple of blades of grass/sedge by the edge of a large pond a few weeks back. It was in the process of metamorphosing and still had a significant tail. Funnily enough, today in my house I came across two of these insects, called Silverfish (order Thysanura), in separate rooms. They quite often occur in human habitations, though I've never seen them before in mine. Was it just a coincidence that I saw my first and second on the same day, or am I witnessing the overrunning of the whole house?

Funnily enough, today in my house I came across two of these insects, called Silverfish (order Thysanura), in separate rooms. They quite often occur in human habitations, though I've never seen them before in mine. Was it just a coincidence that I saw my first and second on the same day, or am I witnessing the overrunning of the whole house? We get a yearly plague of Grapevine moth caterpillars on our ornamental grape. I spotted this Peron's Treefrog (Litoria peronii) just outside our front door just a few minutes ago chowing down on one of the little guys.

We get a yearly plague of Grapevine moth caterpillars on our ornamental grape. I spotted this Peron's Treefrog (Litoria peronii) just outside our front door just a few minutes ago chowing down on one of the little guys. This little guy came in yesterday through the frog rescue service. They're commonly transported around the country in fruit and vegetables.

This little guy came in yesterday through the frog rescue service. They're commonly transported around the country in fruit and vegetables. It looks a bit like a blue-tongue only its tongue is pink. So guess what it's called?

It looks a bit like a blue-tongue only its tongue is pink. So guess what it's called? Yup, a pink tongue. Hemisphaeriodon gerrardii to be precise. It's a nocturnal, largely arboreal skink with impressive hooked claws and a flexible tail for climbing. During frogging forays they are occasionally spotted hanging on happily a few metres up a tree trunk.

Yup, a pink tongue. Hemisphaeriodon gerrardii to be precise. It's a nocturnal, largely arboreal skink with impressive hooked claws and a flexible tail for climbing. During frogging forays they are occasionally spotted hanging on happily a few metres up a tree trunk. In a previous post I showed a photo that, it turns out, is of an adult female paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus.

In a previous post I showed a photo that, it turns out, is of an adult female paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus. Ever been annoyed in the shower by tiny little flying things?

Ever been annoyed in the shower by tiny little flying things? I'm sleepy. Just an image for tonight. It's a small species of native bee that visits my garden frequently, one of the Lipotriches species. I think it's L. excellens, though flavoviridus is another possibility. It's foraging on a Lobelia flower.

I'm sleepy. Just an image for tonight. It's a small species of native bee that visits my garden frequently, one of the Lipotriches species. I think it's L. excellens, though flavoviridus is another possibility. It's foraging on a Lobelia flower. I've been having great fun with my combination of extension tubes (70mm or so) plus my 50mm macro lens racked out to minimum focus. Total reproduction ratio is 2.4:1 on the sensor, meaning that the full frame covers about 10 x 6.5 mm.

I've been having great fun with my combination of extension tubes (70mm or so) plus my 50mm macro lens racked out to minimum focus. Total reproduction ratio is 2.4:1 on the sensor, meaning that the full frame covers about 10 x 6.5 mm. Well that was unbelievably lucky.

Well that was unbelievably lucky.

Blue on black,Don't mean much? Take a look at the colours of the Ulysses butterfly (Papilio ulysses) from Australia's tropics and say that again. The amazing contrast between the two regions of this butterfly's wings is actually teaching us some things about optics that we didn't realise.

tears on a river

Push on a shove,

it don't mean much

- 'Blue on Black', Kenny Wayne Shepherd Band

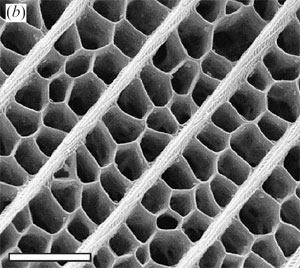

From Vukusic et al. (2004, Figure 2b). This is a scanning electron micrograph of the ridges and latticing on a scale (bar represents 2 μm). While there's black pigment on the surfaces and interspersed throughout the material, this pigment can only absorb so much light. The rest is reflected. But the structure is such that the light actually seems to bounce around in those pits (which are tiny; a thousandth of a millimetre across by my estimate) and get scattered towards the absorbing pigment, some of it getting absorbed each time it encounters the pigment. The end result is an absorbance as high as 95%. This is actually the first time that the use of microstructures to create black colouration has been demonstrated.

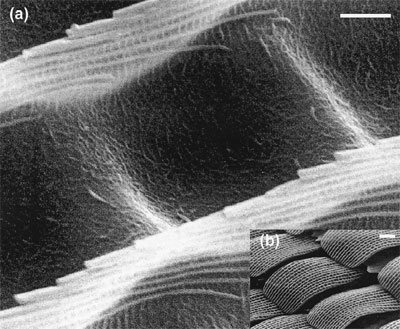

From Vukusic et al. (2004, Figure 2b). This is a scanning electron micrograph of the ridges and latticing on a scale (bar represents 2 μm). While there's black pigment on the surfaces and interspersed throughout the material, this pigment can only absorb so much light. The rest is reflected. But the structure is such that the light actually seems to bounce around in those pits (which are tiny; a thousandth of a millimetre across by my estimate) and get scattered towards the absorbing pigment, some of it getting absorbed each time it encounters the pigment. The end result is an absorbance as high as 95%. This is actually the first time that the use of microstructures to create black colouration has been demonstrated. Now take a look at the fine structure of the blue scales (right; from Vukusic et al, 2001; fig. 3; scale bars: a: 1 μm, b: 20 μm). Those ridges are still there though the complex pits within them are not. So it's not really the surface structure that's responsible for the brilliant azure.

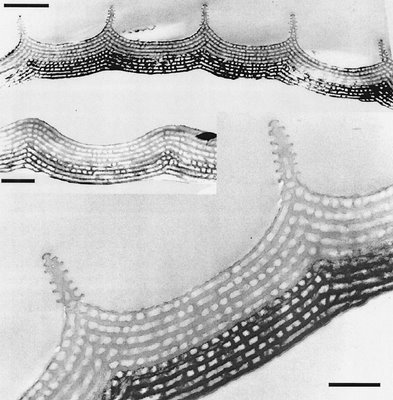

Now take a look at the fine structure of the blue scales (right; from Vukusic et al, 2001; fig. 3; scale bars: a: 1 μm, b: 20 μm). Those ridges are still there though the complex pits within them are not. So it's not really the surface structure that's responsible for the brilliant azure. Also from Vukusic et al, (2001, figure 5, scale bars from top: 3 μm, 1 μm and 1 μm), this final figure shows some cross-sections through the scale. The physics is a bit complicated and I don't understand it fully myself, but from what I gather, the 3D matrix of air-filled spaces (often referred to as a 'multilayer nanostructure') within the scale leads to a phenomenon called 'coherent scattering'. So some wavelengths undergo interference and are 'cancelled out' while others are reinforced (i.e. the blue).

Also from Vukusic et al, (2001, figure 5, scale bars from top: 3 μm, 1 μm and 1 μm), this final figure shows some cross-sections through the scale. The physics is a bit complicated and I don't understand it fully myself, but from what I gather, the 3D matrix of air-filled spaces (often referred to as a 'multilayer nanostructure') within the scale leads to a phenomenon called 'coherent scattering'. So some wavelengths undergo interference and are 'cancelled out' while others are reinforced (i.e. the blue). Found a couple of these cool animals on a field trip recently. No, it's not an earthworm, it's actually a young Blackish Blind Snake (Ramphotyphlops nigrescens). I was reminded of the following great story concerning these beasts.

Found a couple of these cool animals on a field trip recently. No, it's not an earthworm, it's actually a young Blackish Blind Snake (Ramphotyphlops nigrescens). I was reminded of the following great story concerning these beasts. It's a busy time of the year with end of semester projects being wrapped up and assignment due dates looming. Don't even mention exams.

It's a busy time of the year with end of semester projects being wrapped up and assignment due dates looming. Don't even mention exams. I had a great long weekend in the field - spending some time up on the mid-north coast around Smith's Lake. Lots of interesting animals and even a few plants that I had to admit were very attractive and interesting.

I had a great long weekend in the field - spending some time up on the mid-north coast around Smith's Lake. Lots of interesting animals and even a few plants that I had to admit were very attractive and interesting. Next a species which always thoroughly amazes me. It's the aptly named Flying Duck Orchid (Caleana sp., possibly C. major). I've seen these guys only once before but was happy to find them again, their flower stalks sprouting out of the disused 4WD track.

Next a species which always thoroughly amazes me. It's the aptly named Flying Duck Orchid (Caleana sp., possibly C. major). I've seen these guys only once before but was happy to find them again, their flower stalks sprouting out of the disused 4WD track. In similar places to the duck orchids were a few Beard Orchids (Calochilus sp.)

In similar places to the duck orchids were a few Beard Orchids (Calochilus sp.) Finally, somewhat inconspicuous in amongst the grass, these tiny onion orchids (Microtis sp.) were in good numbers. Each of those little blooms is tiny, less than a centimetre long!

Finally, somewhat inconspicuous in amongst the grass, these tiny onion orchids (Microtis sp.) were in good numbers. Each of those little blooms is tiny, less than a centimetre long! For today, not only do we have another Litoria peronii embryo (left), but a rather smaller beastie.

For today, not only do we have another Litoria peronii embryo (left), but a rather smaller beastie.

Well here's another little embryo photo, taken today. I'm really getting into this! For the record this is Litoria peronii, the Perons Treefrog. Read earlier post.

Well here's another little embryo photo, taken today. I'm really getting into this! For the record this is Litoria peronii, the Perons Treefrog. Read earlier post.